Results-based management in the budget context in WHO

Summary

WHO has planned on the delivery of results since the 1970s. However, the explicit adoption of results-based management began in the 1990s so that Member States could exercise control of WHO’s priorities based on the results to be delivered and the funding required to do so.

This has been very hard to manage in an environment where the Programme budget is financed by almost up to 80% at times by voluntary contributions which are rarely flexible, predictable or sufficiently sustainable to ensure that results can be delivered as planned and approved. Nonetheless, significant improvements in resource allocation and alignment have been made since the 1990s.

Assessments have recognized the ambition set and progress made while stressing the need to ensure full internalization and ownership.

Distinct improvements have been recognized in country prioritization, coordination of technical support across different levels, and resource allocation. The main challenges at this point are sustainable financing and supporting a long-term vision and the need for change at a strategic level.

A Brief Background

Academic and theoretical definitions vary but results-based management (RBM) is broadly understood as a focus on outputs, outcomes and impact as the result of planning. It is defined by the UN Development Group as, “a management strategy by which all actors, contributing directly or indirectly to achieving a set of results, ensure that their processes, products and services contribute to the achievement of desired results (outputs, outcomes and higher level goals or impact). The actors in turn use information and evidence on actual results to inform decision making on the design, resourcing and delivery of programmes and activities as well as for accountability and reporting” [1].

In terms of the Programme budget in WHO, as in other parts of the UN system, it has often been conceptualized as a move from planning capacities required in line with resources available, to planning from the bottom up to deliver specific and measurable results. The concepts of results-based budgeting and results-based management became increasingly popular in the broader UN system from the 1990s as Official Development Assistance (ODA) became a significant source of financing for the multilateral sector. These voluntary contributions made advance planning of organizational capacity essentially redundant since the precise resource levels were simply not known in advance.

Hence the strategic approach was to plan for the results to be delivered, against which the financing could be received. This permitted Governing Bodies to approve organizational priorities and directions without having to and/or being able to commit the required resources in advance.

From a secretariat’s viewpoint, this provided another benefit which gained more prominence. It meant that an organization would plan for measurable impacts for which it would be held accountable but which it could also (at least in theory) control. Rather than budgeting for a basic capacity level and then trusting that this would be sufficient to deliver whatever mandate was entrusted, an organization could budget and plan for the delivery and impact of that work. This became the overriding logic which justified the move to RBM.

The History of RBM in WHO

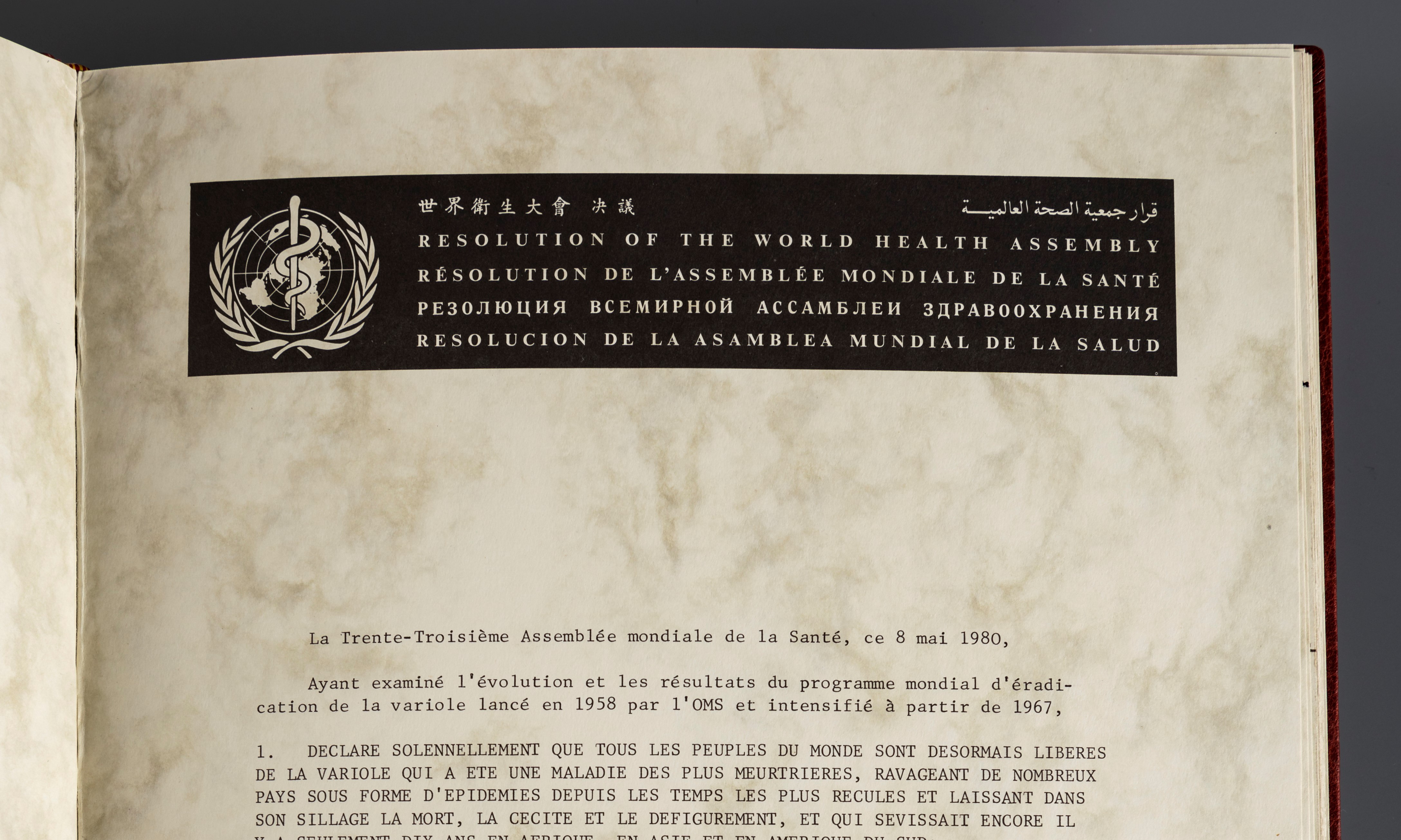

Conceptually, RBM has informed WHO’s management approach for decades. Resolution WHA30.23 in 1977 began by, “Recalling resolution WHA25.23, which adopted for WHO a form of programme budget presentation based on the principles of a programme-oriented approach to planning, budgeting and management” [2]. In 1988, the report of the Programme Committee of the Executive Board on the Management of WHO’s Resources (EB83.R22) noted that, “the Programme Committee strongly endorsed continuation of the practice of issuing "country planning figures" as a starting point for the joint government/WHO programme review and programme budgeting process taking place in every region” [3].

In practice, this often applied more to in-country government consultations in the preparation of results planning, and was limited in its application at the Regional Office and Headquarters levels. Nor was it apparent in the Programme budgets submitted for adoption.

Nonetheless, the concept had been recognized. In 1989, in its report to the WHA on the proposed Programme budget 1990-1991, the Executive Board noted, “as reflected in PB/90-91, that, according to information received so far, the expected resources from "Other Sources" for the current biennium and for 1990-1991, for the first time in the history of WHO, already exceed the provision for the regular budget. This has important implications for the future work of WHO” [4]. Faced with the need to plan for an increasingly voluntary contributions-financed budget, it was also reported that, “The Board shares the concern expressed by the Health Assembly and the regional committees that WHO's technical, human, material and financial resources should be used in the most efficient and effective manner at all organizational levels, and by Member States, in accordance with the global, regional and national policies and strategies, with due regard to the agreed decentralized policy, programme and fiscal arrangements, and with maximum impact on the health of the people of the world” [5].

This would ultimately lead to the explicit move to results-based management from 2000 which was a response to the serious concerns of Member States that the previous, resource-based model followed up to the late 1990s left the real prioritization of WHO’s work open to the highest providers of voluntary contributions. Hence the move to focus on the results to be achieved before the resource levels which would need to be approved to deliver them. The strong endorsement of this approach by Member States grew with the increasing emphasis over the next two decades on delivering results at the country level. It made much more sense to plan for the results to be achieved within a country than to start from the basis of what resources might (or might not, if reliant on voluntary contributions) be available. Instead, the planning of resources would follow the definition of results and their prioritization. This was endorsed by Member States with their explicit approval of Programme budgets which included the explicit integration of a global voluntary contributions envelope by result into the approved Programme budget 2000-2001. This was refined in the Programme budget 2006-2007 to provide assessed contributions (AC) and voluntary contributions (VC) envelopes by result for each Major Office. From the Programme budget 2014-2015 onwards, a single envelope by result for each Major Office has been provided without a distinction between AC and VC. No Programme budget has been costed or planned by Organizational structure (beyond disaggregation by Major Office) since 2000-2001.

As a consequence, no Major Office has been able to plan its results on the basis of a pre-determined financing envelope and so results-based budgeting has been essential. With a mindset already encouraged towards RBM, and a staged evolution of budgeting practices, this was not a revolution so much as an evolution in practice. The Director-General wrote, in her introduction to the proposed Programme budget 2000-2001, “You can imagine the difficulty in estimating our voluntary income up to as much as three years ahead. Even our techniques for this estimation are still at a very early stage, especially in the regions. I therefore decided that we had to show targets, built upon what each area considered was needed to get the work done, but tempered with an appraisal of what we might realistically achieve.

“This is in contrast to what was done in the past, which was to show only what was known at the time of budget preparation - which was always less than what actually came in - and which led to almost no discussion of extrabudgetary resources by our governing bodies. This new approach has already stimulated the type of interest and debate that we really need and welcome.

“More important, however, is the accountability for results. Increasingly, we want to be judged by what we do and what we produce and not just by how much money we have. This calls for clear statements of mission, objectives, and tangible and wherever possible, measurable indicators of success. We have attempted to do that in the budget document, but a lot more work remains to be done, and will be done, in this area” [6].

Financing

It quickly became clear that RBM was making progress. The Programme Budget 2002-2003 Performance Assessment Report described how, “WHO’s governing bodies (including the regional committees), together with WHO partners and donors, commended the Organization’s move to establish results-based budgeting within a broader framework of results-based management. For the first time, assisted by performance monitoring, evaluation and reporting on expected results, the governing bodies were able to observe the results that the Organization had committed itself to achieving, thereby making WHO more transparent and accountable. Furthermore, senior staff began increasingly to manage in terms of results, drawing on and applying knowledge gained during implementation” [7].

Various elements were identified for improvement at the same time, notably increased coordination across all three levels of WHO, closer integration of global and country priorities, the relative weakness of indicators, and the needs for stronger coordination and training. None, however, gained the same prominence as the question of financing and how a lack of predictable resources seriously hindered resource allocation and, by default, the effective implementation of results-based budgeting. The same document claimed that, “The challenge is to ensure that actual allocations at the different levels reflect the resources required to achieve the contribution of regional and country offices to Organization-wide expected results that have been agreed upon collectively” [8]. This became a recurring theme in budgeting and planning documents prepared for the WHA, Executive Board and PBAC by both Member States-led Committees and the Secretariat.

The Secretariat responded through a number of initiatives, notably the establishment of the XM account in 2006 (predecessor of the current Core Voluntary Contributions Account) and the establishment of the Advisory Group on Financial Resources in 2007, both of which were presented to Member States as significant achievements in the performance assessment of the Programme budget 2006-2007 [9]. While the latter proved relatively ineffective (although subsequently re-constituted with revised terms of reference as the current Resource Allocation Committee in 2020), the former has remained a key part of flexible financing since then. Although the alignment of resources with planned results has never shifted dramatically from one biennium to the next, the trend over the past two decades has demonstrated a broad achievement in improving the situation.

Nonetheless, this remained a consistent, and probably the most serious, hindrance to effective RBM in WHO since its formal adoption in the 1990s. Although highlighted to Member States in almost every Programme budget performance assessment since 2002-2003, increases in “sustainable financing” were largely regarded as synonymous with increases in AC, which proved politically unacceptable to too many Member States to be addressed systematically. In addition to incremental improvements in the alignment of resources, qualitative improvements were introduced in terms of stronger coordination and accountability frameworks(e.g. Technical Expert Networks, Output Delivery Teams). While these were valuable, the question of financing was never seriously addressed until the establishment of the Working Group on Sustainable Financing following the recognition in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, that WHO had to be strengthened and that the question of financing aligned with the RBM model would be intrinsic to that.

Qualitative Assessments

As described above, many improvements have been introduced to strengthen RBM besides the question of how best to finance the adopted budget in such a way as to maximize its use in support of RBM. In any case, there is more to effective RBM than simply ensuring that those using it have sufficient resources. Furthermore, unlike financing, the extent to which the Secretariat alone can take effective action to strengthen RBM is considerable, even if not all-encompassing, and so improvements have been progressively introduced on a continual basis.

Curiously, no comprehensive Organization-wide assessment of RBM was conducted until an Independent Evaluation of WHO’s Results-Based Management Framework was mandated at the end of 2021. WHO had been previously evaluated by the UN Joint Inspection Unit in 2017 as part of an evaluation across the UN system but despite evaluations of different elements related to RBM, as described below, this is the first comprehensive review to be conducted where the expressed, “purpose of the evaluation will be to assess, as objectively and systematically as possible, the application of results-based management principles within WHO as a vehicle for helping steer the Organization toward maximum results in the service of the Organization’s global health mandate [10]”.

Nonetheless, as the inception paper of the independent evaluation notes itself, RBM does not yet benefit from a universally accepted definition. In WHO, the focus of RBM has been predominantly on accountability and communications (with a weaker focus on decision-making and learning aspects) in conjunction with a strong focus on value for money. Partly stemming from this lack of clarity, the reform process initiated in 2011 focused, among other elements, on strengthening RBM. Three evaluations were conducted in 2012 [11], 2013 [12] and 2017 [13], the first by the External Auditor (Comptroller and Auditor General of India), the latter two by PricewaterhouseCoopers SA. The reports are quite extensive, but some key messages are notable.

The 2012 audit noted that, “Though the reform process started due to constraints faced by WHO in the area of funding, it was dynamic enough to expand to other areas, specially priority setting, where WHO is facing challenges in implementing its mandate” (page 3). A key message was the need for the general acceptance of and engagement in the RBM process across the Organization: “Wide ranging changes require acceptance at various levels. An advocacy plan, to explain the implications of the change strategy, identification of change agents and a detailed change management plan would be required to implement the plan of action, after the approvals are received from the requisite authorities” (page 5).

The 2013 report was particularly blunt in stating that, “The strengthening of results-orientation, accountability, internal controls and risk management throughout the Organization represents a major cultural shift which will require significant behavioural change at all levels of the organisation. To achieve this, the Secretariat will need to go beyond the current focus on policies, procedures and systems” (page 9). It also claimed that, “The culture that WHO is seeking to implement through reform is one that is results-oriented, takes into account transversal ways of working across organisational silos, and adheres to a risk management mindset. It is this culture, however, which is needed in the first place to drive the implementation of the reform successfully” (page 11). The report recommended increases in capacity and training and moving from an event-driven approach to one focused on progress against defined results.

By 2017, significant progress was being observed. The evaluation from that year reported that, “First and foremost, significant headway has been made in the approach to planning and prioritising activities based on country needs. This includes notably increased alignment of Country Cooperation Strategies with national health strategies and plans, as well as the allocation of 80% of country office’s budget on a maximum of 10 priorities agreed with each Member State.

“Also, some improvements can be observed in the delivery model at the three levels of the Organization, most notably the implementation of programme and category networks to improve the coordination across the Secretariat and in the progressive crystallisation of the respective roles of each level of the Organization.

“Finally the period under review has seen a sharp increase in the transparency of resource allocation and financing, notably through the implementation and ongoing refinements of the web portal, as well as some improvements in definition of results and standardisation of outputs and deliverables across the Organization” (page 8).

In all instances, the imperfections of sustainable financing and resource allocation remained areas for improvement.

Unresolved Issues

Two particular issues have arisen with the adoption of RBM which have not, to date, been fully resolved.

Governance and Control

This has been a consistent problem raised repeatedly up until, and including, the Working Group on Sustainable Financing over the course of 2021 to 2022. If Member States approve an expenditure level but do not take responsibility for its financing, then the question becomes whether the ultimate authority for what the Organization does lies with the Member States of the WHA, who have approved the expenditure for the delivery of a result, or the donors who have contributed the resources. In theory, the former istrue under RBM since the results are the ultimate objective, but this is somewhat hollow without the resources which underpin it.

Under WHO’s Financial Rules and Regulations [14], the authority is technically clear:

“15.1 Neither the Health Assembly nor the Executive Board shall take a decision involving expenditures unless it has before it a report from the Director-General on the administrative and financial implications of the proposal.

15.2 Where, in the opinion of the Director-General, the proposed expenditure cannot be made from the existing appropriations, it shall not be incurred until the Health Assembly has made the necessary appropriations.”

In other words, the Member States authorize expenditures in the Programme budget (approved through the Appropriation Resolutions) and any other expenditure through an explicit decision to do so. This worked well enough in an era when the Programme budget was essentially approved as the totality of the sustainable Regular Budget. Any additions would be approved explicitly in addition and the resources would need to be appropriated as a result.

However, as described above, under RBM, the budgets evolved as follows:

- 2000-2001: approval of a global VC envelope in addition to Major Office RB envelopes

- 2006-2007: approval of Major Office envelopes for both AC and VC

- 2014-2015: approval of Major Office envelopes without distinction of AC and VC

Consequently, Member States’ control over which results they were approving in the Programme budget became subject to the level of resources made available. RBM had to be taken almost on trust or at best applied with rigorous oversight of its application by the Secretariat.

Theory of Change

Since 2000, WHO has implemented five GPWs. In summary:

| GPW | Period Covered | Results | Nature |

| 9 | 1996-2001 | Policy directions/ programmes | Horizontal |

| 10 | 2002-2005 | Areas of Work | Vertical |

| 11 | 2006-2015 | Strategic Outcomes/ Org-wide Expected Results | Horizontal |

| 12 | 2014-2019 | Categories/ Programme Areas | Vertical |

| 13 | 2018-2025 | Strategic Priorities/ Outcomes | Horizontal |

The trends are fairly evident but indicate a potential concern in terms of strategic planning and particularly for RBM. The definition of RBM used by the UNDG (and others) refers to the delivery of sustainable impact which is measurable. When a results structure changes as WHO’s can do from one GPW to the next, then a longer-term baseline or measurably sustainable results are not easy to define. WHO’s RBM model works in the short- to medium-term but in the longer term, it can be hard to identify key achievements, at least on a scientific basis. This is being addressed with the renewed focus on science and data analytics but it has resulted in several and continuing dialogues on the efficacy of RBM in WHO because the strategic goals are confusing for Member States to discern.

The solution needs to come from both the Secretariat and Member States in terms of long-term vision. For example, consideration must be shown in the approval of a new GPW as to what progress has already been achieved and what changes are ongoing, which the new GPW should support. There is no harm (indeed, there is benefit) in learning from previous successes and failures but simply re-defining results from a zero basis does not demonstrate a comprehensive, strategic approach. By way of contrast, an example of best practice is probably the UN Sustainable Development Goals. While defining a new, strategic direction, these were defined in order to build on both the successes and shortcomings of their predecessors, the Millennium Development Goals. If Member States approve strategies at this level of change theory, then the Secretariat should be able to deliver what they ask for with the lessons which are being learned at present. Learning has been identified by some as a key component of RBM and it is one which could be strengthened in WHO to achieve increasingly robust results.

Conclusion

In a qualitative sense, WHO has been demonstrating behaviour at least influenced by an RBM mindset since the 1970s. This has been put into practice since the 1990s with an explicit move to results-based budgeting from 2000 onwards.

The adoption of RBM has been somewhat piecemeal and variable across the Organization but various steps taken by the Secretariat, influenced not least by collaboration with and learning from other members of the UNDG, have helped to integrate it much more into the Organizational culture than was the case one or two decades ago.

Member States have been kept fully appraised of RBM developments through Programme budget reports, the various studies conducted and now the Independent Evaluation of WHO’s Results-Based Management Framework. Their guidance and support continue to be strong with the increasing focus on country-level results over the past decade, as well as in the capacity of significant donors in the case of several Member States.

Sustainable financing has been arguably the greatest challenge to effective RBM. If this is now addressed, then the remaining and significant challenge outside the Secretariat’s full control is the question of effective, strategic governance.

RBM is the management approach adopted explicitly by the Organization since 2000. As something of an early adopter in the UN system, WHO is often regarded as a strong example of the practice in that system. With sufficient experience and data now available, the main question for both Member States and the Secretariat is not simply whether the latter is employing it effectively, but how the Organization as a whole can make it work to its fullest potential.

References

[4]https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/162897/EB83_45_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, para 12

[5] Ibid, para 15

[8] Ibid

[9] Microsoft Word - A61_19-en.doc (who.int), paras 75 and 76

[10] Independent Evaluation of WHO’s Results-Based Management Framework, page 36