Attacks on Health Care:

Three-year analysis of SSA data (2018-2020)

The impact of attacks on health care1 in Fragile, Conflict-affected and Vulnerable (FCV) settings2 goes well beyond endangering health providers. Reduced capacity, interrupted services and loss of health care resources deprive vulnerable populations of urgently needed care, undermine health systems and jeopardize long-term public health goals.

As the world struggles with the COVID-19 pandemic, protecting health care where health systems are the most vulnerable has become more important than ever. Ensuring the right to access health care for everyone, everywhere is not only at the core of WHO’s commitment to achieve better health but also a stepping stone to a reaching the Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs.

Here, the analysis of publicly available data collected via WHO’s Surveillance System for Attacks on Health Care (SSA) from 2018 to 2020 presents a global overview of attacks on health care, the resources that they affected and their immediate impact on health workers and patients.

The results demonstrate that attacks on health care are highly context-dependent. The occurrence, nature and dynamics of attacks are closely related to changes in the operational context of the local health response. Such changes may include the emergence of new crises, intensification of conflicts, ceasefires or the deterioration of community acceptance.

In addition, changes in the operational contexts of individual FCV countries or territories where attacks are more prevalent play an important role in driving global-level patterns of attacks on health care. For this reason, it should be noted that the results of this analysis are not representative of country-level trends and only provide a global overview of all verified incidents reported through the SSA. However, this analysis can be replicated at country-level using the SSA dashboard’s data export function.

Key findings

- Health personnel is the most frequently affected health resource;

- Attacks on health care were associated with a higher proportion of deaths in 2020;

- Changing contexts are an important driver for yearly differences in the data;

- Reports of attacks on health care involving psychological violence, threats of violence or intimidations have decreased in 2020;

COVID-19 impact

- Changes in the number of reported attacks on the SSA preceded the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Attacks affecting health facilities, transport and patients became more frequent after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Attacks on Health Care initiative

In 2012, World Health Assembly Resolution 65.20 was adopted and called on WHO’s Director-General to provide global leadership in the development of methods for the systematic collection and dissemination of data on attacks on health facilities, health workers, health transport and patients in complex humanitarian emergencies. WHO subsequently created the Attacks on Health Care (AHC) initiative to collect evidence, advocate for the end of attacks, and promote best practices for protecting health care.

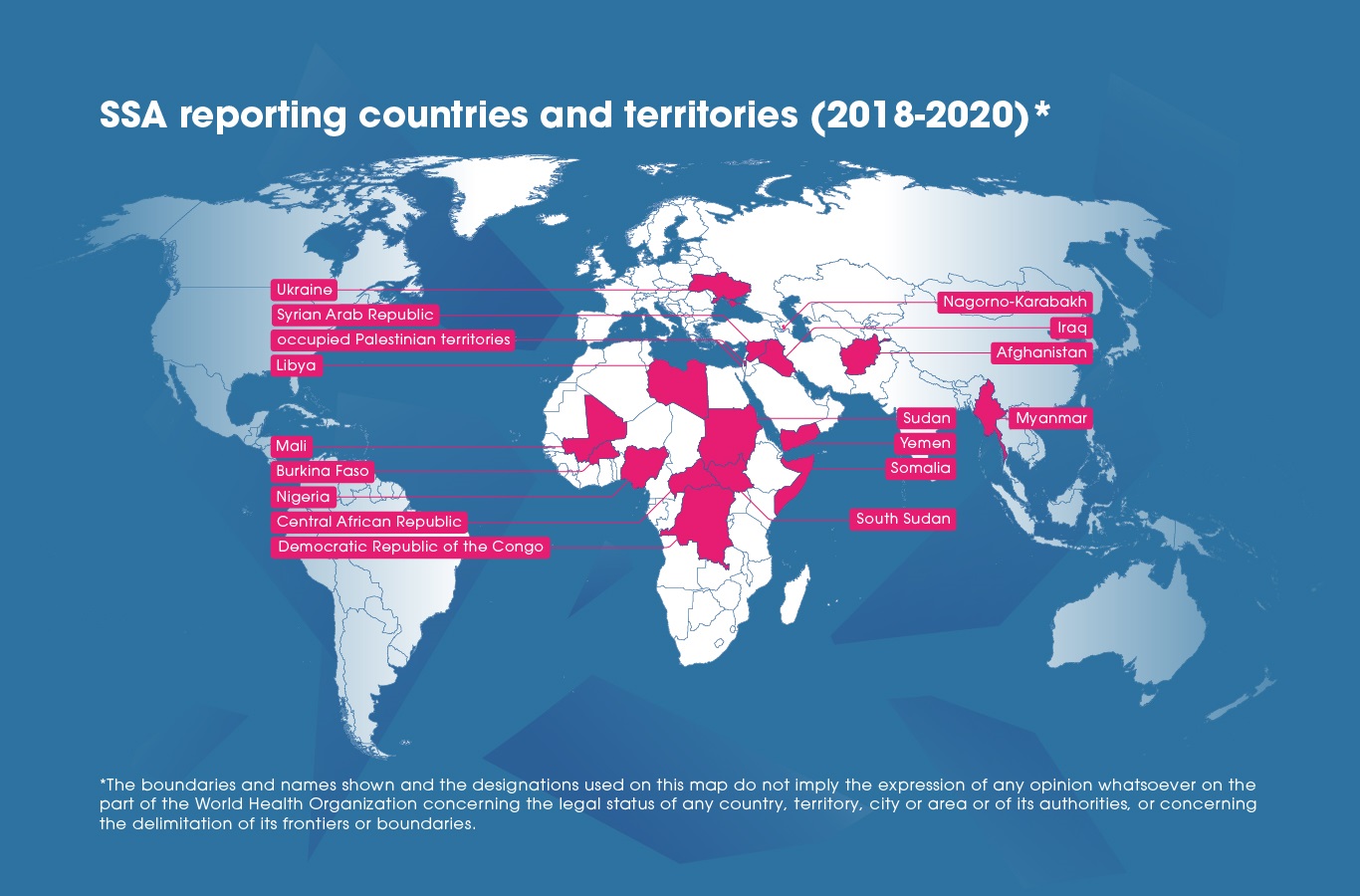

Collecting data of attacks on health care

WHO’s Surveillance System for Attacks on Health Care (SSA) collects standardized primary data about attacks against health care in FCV settings. WHO works closely with partners on the ground in 17 countries and territories to gather relevant information about incidents, which is then verified by the WHO Country office. A detailed methodology for the collection of data via the SSA is available here.

Incidents reported via the SSA include ‘any acts of verbal or physical violence or obstruction or threat of violence that interferes with the availability, access and delivery of curative and/or preventive health services during emergencies’3. In this definition, both ‘higher-impact’ attacks on health care – such as bombings – and ‘lower-impact’ attacks – such as verbal threats – are included.

Magnitude of the problem

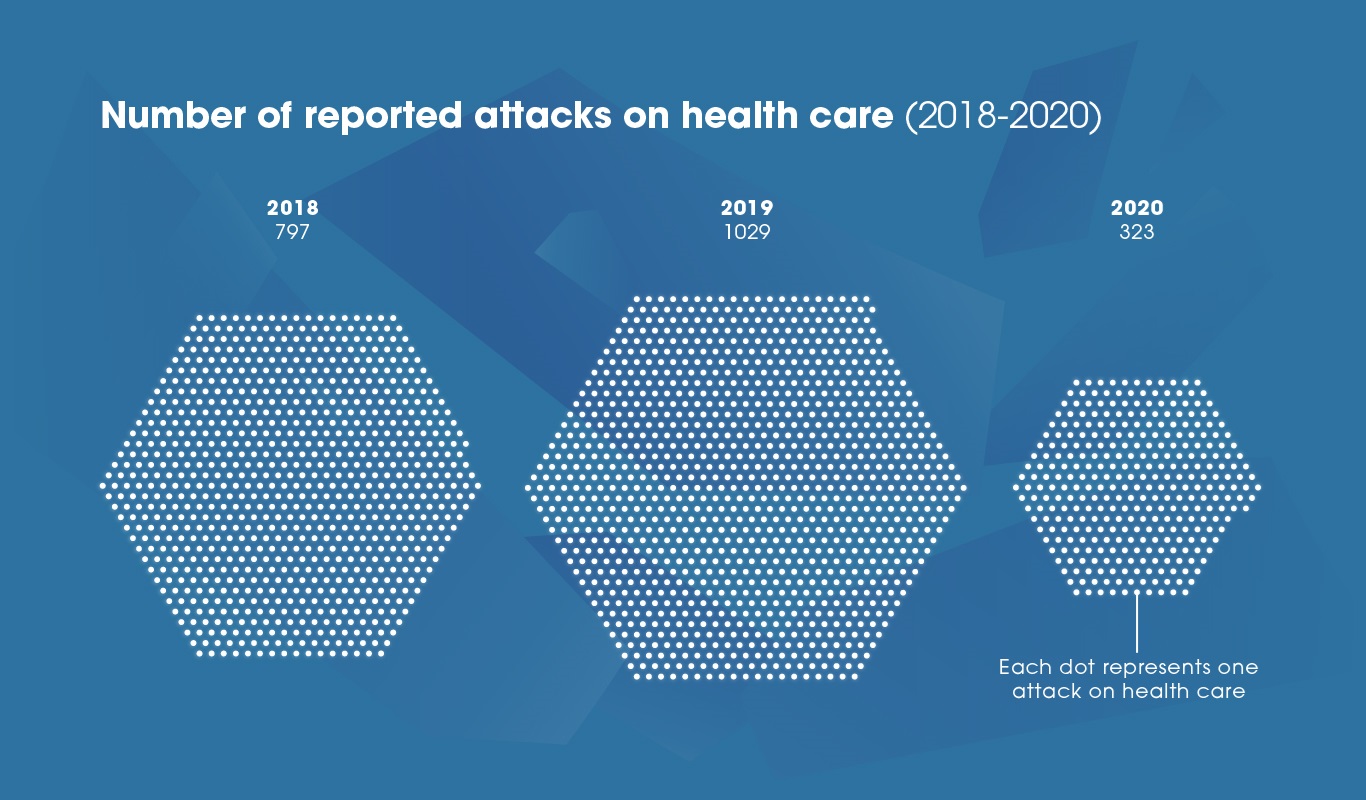

As of 21 April 20214, the SSA recorded 797 attacks on health care in 2018, 1029 in 2019 and 323 in 2020 across 17 countries and territories.

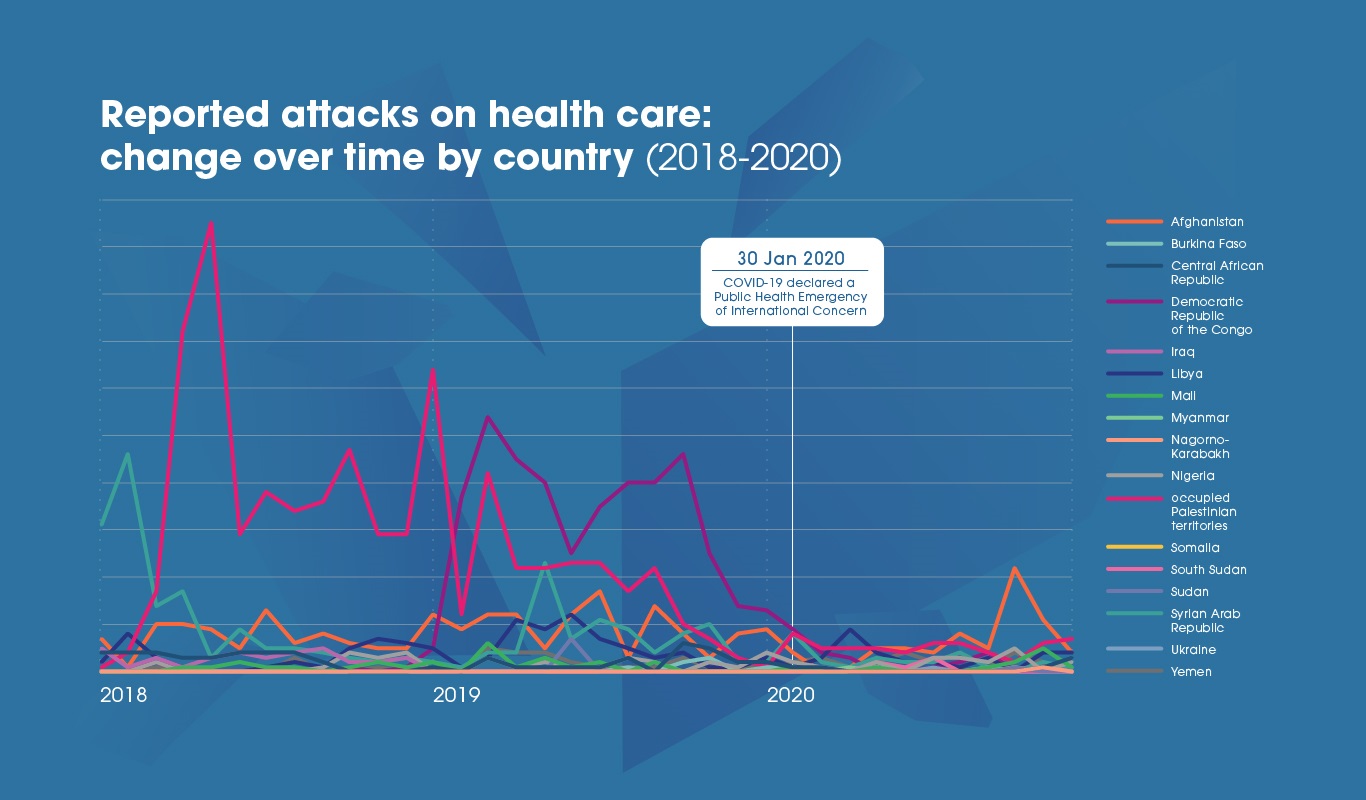

Further analyses into patterns of attacks before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that the number of reports on the SSA fell before the pandemic. The data collected during the COVID-19 crisis showed that in the majority of FCV countries and territories already confronted with high volumes of attacks on health care there was no marked change in the number of reported incidents during that period.

Rather, reports of attacks on health care became markedly less frequent starting mid-2019. Data collected via the SSA between 2018 and 2020 shows that the number of reported attacks dropped during the last quarter of 2019 and reached

its lowest during the first quarter of 2020.

Changes in the operational contexts of a limited number of countries and territories with FCV settings were one of the main drivers for yearly differences in number of reports. For example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt) accounted for two thirds of all reported attacks in 2019 with respectively 406 and 267 reports. It is notable that when both are removed from calculations, the number of attacks reported in 2020 is not as markedly lower than in previous years5.

Between 2018 and 2020, DRC faced the world’s second largest Ebola outbreak during which numerous incidents of attacks on health workers and Ebola treatment centres6 were reported. Many of these attacks were motivated by mistrust and misunderstanding of the disease in an already vulnerable setting. The number of reports fell after the scaling down of the response towards the end of 2019.

In oPt, an unprecedented number of attacks on health care was recorded in the context of the 2018-2019 demonstrations in the Gaza Strip7, known as Gaza’s “Great March of Return”8. After the demonstrations ended towards the end of 2019, reports of attacks on health care became markedly less prevalent.

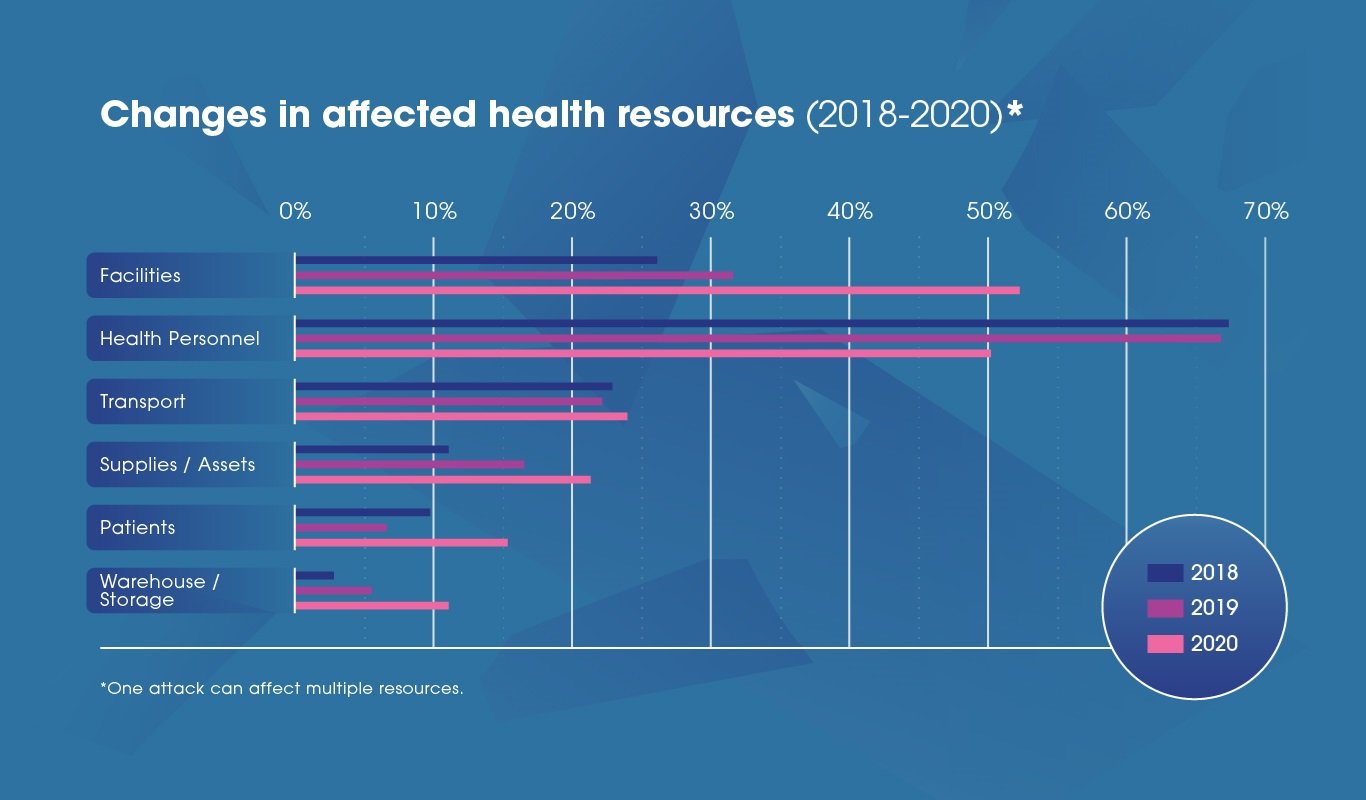

Health resources affected by attacks

Overall, health personnel is the most frequently affected health resource9. In 2018 and 2019, attacks on health care impacted health personnel in about two thirds of reported incidents. In 2020, reported attacks affecting health personnel were less frequent than in previous years, while attacks affecting health facilities became more frequent.

Attacks affecting health facilities, transport and patients have been proportionally more frequent after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it should be noted that considerable differences exist between reporting countries and territories. Some have seen an increase in reports of attacks affecting health workers.

Changes in the proportion of attacks affecting health personnel have in part been driven by patterns observed in a limited number of countries and territories.For example, oPt has seen a significant downturn in attacks affecting health workers during the 2020 reporting period. With the territory accounting for 21% of all reported attacks affecting health personnel during that year, the change in patterns of attacks in oPt is likely to have driven global results.

Impact of attacks on health workers and patients

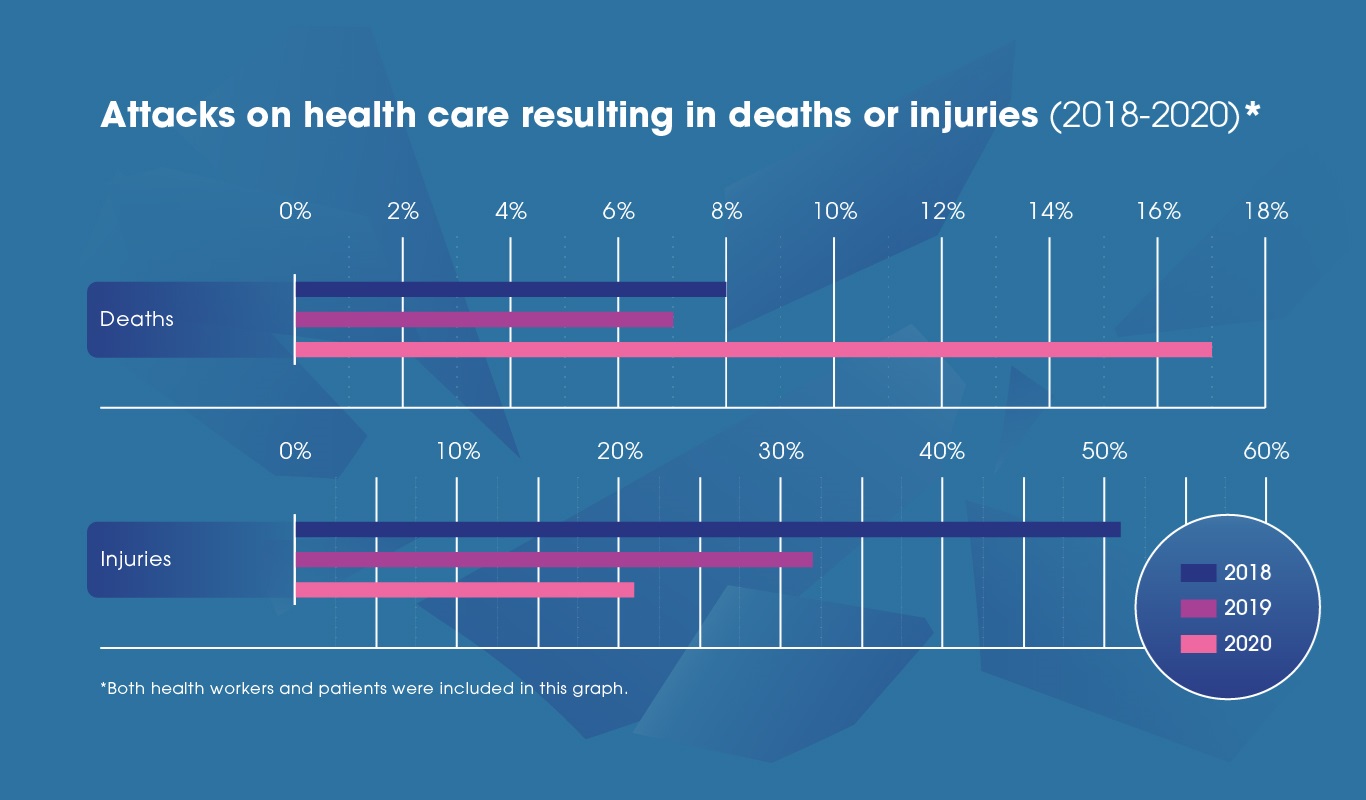

Health and care workers and patients are particularly vulnerable to attacks on health care where there is instability. In 2020, one out of six incidents have led to a patient or health worker’s loss of life.

Despite less reports of incidents in 2020, these were associated with a higher proportion of deaths than in previous years. The proportion of attacks on health care resulting in at least one loss of life reached 17% in 2020, a marked increase compared to previous years. On the other hand, the proportion of attacks leading to at least one injury has steadily decreased over time.

Changes in the operational contexts of a few countries and territories were one of the main drivers for the increased proportion of incidents resulting in deaths. This was most noticeable in oPt and DRC where the percentage of such incidents respectively increased from 0% to 15% and 2% to 28% in 2020. Nonetheless, some settings have seen a decrease in number of attacks resulting in a loss of life. This includes Afghanistan (22% in 2019 to 10% in 2020) and the Syrian Arab Republic (18% in 2019 to 11% in 2020).

Types of attacks on health care

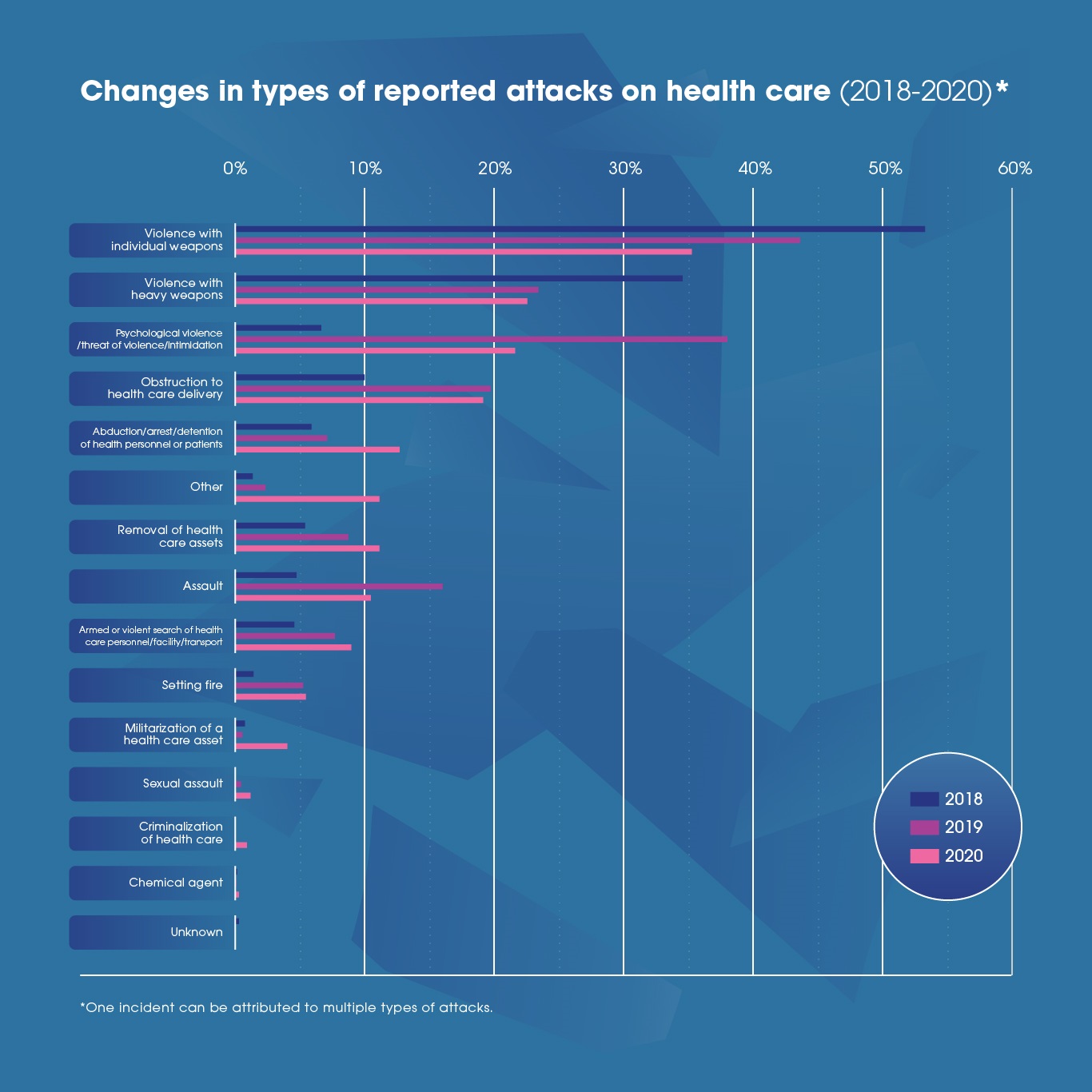

The leading types of attacks on health care across the three years pertain to individual weapons10 use, followed by heavy weapons11 and psychosocial violence12. While individual and heavy weapons violence accounted for a vast majority of reports on the SSA in 2018, lower-intensity attacks have become more represented in the data over time.

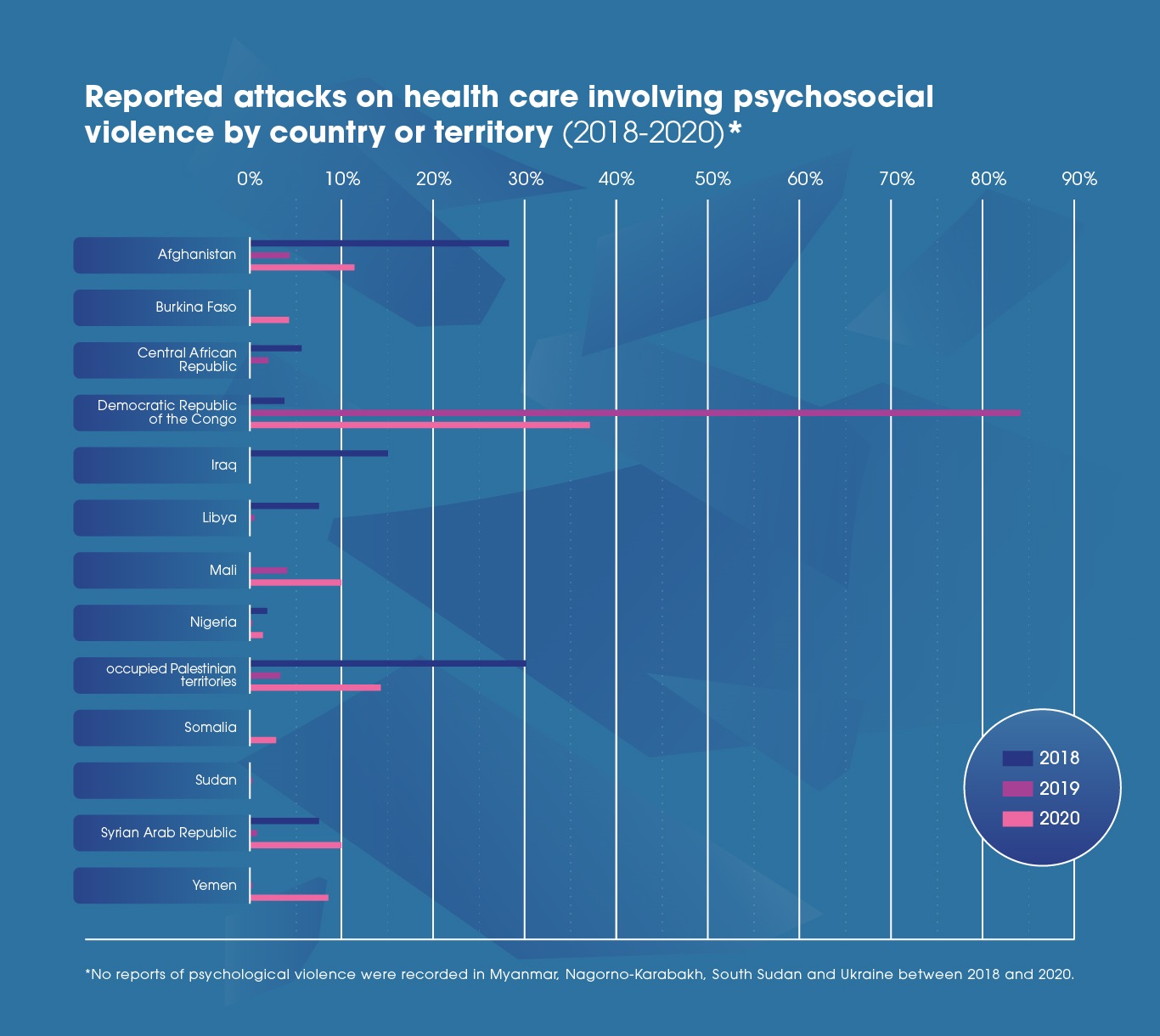

The proportion of attacks on health care involving psychological violence, threats of violence or intimidations have seen a 9% reduction in 2020. In 2019, 392 reports of psychological violence, threats of violence or intimidations were recorded on the SSA, while respectively 53 and 70 reports of this type were recorded in 2018 and 2020. These accounted for 5% of all reported attacks in 2018, 22% in 2019 and 13% in 2020.

Changes in the operational contexts of a limited number of countries and territories had a considerable impact on the reporting of psychological violence, threats of violence or intimidations. For example, reports of psychological violence from DRC accounted for 84% of all reported psychological violence in 2019. After the scaling down of the Ebola health response towards the end of 2019, reports of such attacks became markedly less frequent. When DRC is removed from calculations, yearly differences are reduced13.

Once again, changing contexts were one of the most important drivers for yearly differences across types of attacks. Yet, it is notable that considerable differences between reporting countries and territories persist. For instance, reports citing violence with heavy weapons decreased considerably in settings such as the Syrian Arab Republic (87% in 2018 to 36% in 2020). At the same time, this type of attack became more frequent in other settings, including the State of Libya (8% in 2018 to 39% in 2020) and DRC (1% in 2019 to 42% in 2020).

Next steps

Although the Surveillance System for Attacks on Health Care is relatively new, this analysis shows that its data can already be used to inform operations in FCV countries and territories.

Considerable variation between settings poses a significant challenge to the identification of trends at global level. For this reason, WHO strongly encourages country-level research and analyses to better understand the nature, dynamics and impact of attack on health care in their context.

This global-level analysis raises a number of questions that urgently need to be addressed to improve the operational response to attacks on health care and better protect health care. The questions below provide a few suggestions for country-level research and analyses that would considerably contribute to the design of operationally relevant prevention, protection and mitigation strategies, as well as better support programmes for affected health workers and patients:

- Which prevention, protection and mitigation strategies are both feasible and effective in reducing attacks on health care and their impact?

- What is the association between patterns in types of attacks and consequences in the field?

- What factors are likely to trigger or mitigate different types of attacks on health care?

- What are the short- and long-term consequences of attacks on health care on service provision, health care workers’ psychosocial health or populations’ well-being?

- What are the underlying reasons for observed patterns of deaths and injuries over time?

WHO is currently working closely with partners in reporting countries to conduct operational research on the impact of attacks on health care and mitigation measures. This research work aims to improve knowledge of interventions, strategies or tools that

can enhance the quality, effectiveness or coverage of the health response in FCV settings affected by attacks on health care.

Conclusion

Violence continues to plague access to health care in settings where it is most needed. Health care provision should always be safe anytime, anywhere regardless of the context in which it is delivered. Yet, health workers, facilities and other health resources are too often affected by attacks on health care in fragile, conflict-affected and vulnerable settings.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has further compounded to the challenges faced by FCV settings and caused a shift in patterns of violence. The pandemic has brought unprecedented attention to the acts of violence that the health response is exposed to. It is therefore important to emphasize that changes in patterns of attacks on health care are to be expected whenever a major event or crisis of any kind occurs.

This global-level analysis illustrates the highly contextual nature of attacks on health care, and the importance for research and analyses on this topic to maintain a strong focus on local contexts. WHO strongly recommends reproducing this analysis in countries to better understand trends of attacks on health care at country-level.

WHO continues to work closely with partners on the ground to collect data, document good practices and advocate for the protection of health care in complex humanitarian emergencies. WHO is committed to expanding and refining its efforts the collect data on the incidence and types of attacks, including in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additional resources

References:

[1] WHO’s definition of Attacks on Health Care: Any act of verbal or physical violence or obstruction or threat of violence that interferes with the availability, access and delivery of curative and/or preventive health services during emergencies

[2] While there is no widely accepted global definition, fragile, conflict-affected and vulnerable settings are generally seen to include those experiencing humanitarian crises or prolonged disruption to critical public services, significant armed conflict, extreme adversity or acute, protracted or complex emergencies.

[3] WHO’s definition of attacks on health care

[4] The data was exported on 21/04/2021; minor variations with the current online dashboard are possible due to delays in verifications of incidents.

[5] After removing oPt and DRC from calculations, the number of reported attacks is 362 in 2018, 356 in 2019 and 228 in 2020.

[6] Surveillance System for Attacks on Health Care (2021)

[7] Attacks on health care during the Great March of Return in Gaza (WHO Regional Office for Eastern Mediterranean, 2019)

[8] Report of the independent international commission of inquiry on the protests in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (United Nations Human Rights Council, 2019)

[9] Health resources monitored on the SSA include: health personnel, facilities, transport, patients, supplies and warehouses.

[10] Individual weapons violence: violence with a weapon that does not require more than one person to use, such as knives, bricks, clubs, guns, grenades and improved explosive devices (IED).

[11] Heavy weapons violence: violence with a weapon that requires more than one person to use such as firearms, tanks, missiles, bombs, mortars.

[12] Psychosocial violence: Emotional abuse, such as insults, belittling, humiliation, intimidation, or threats of harm. The explicit declaration of a plan, intention or determination to inflict harm, whether physical or psychological.

[13] After removing DRC from calculations, reports of psychological violence, threats of violence or intimidations accounted for 5% of all reported attacks in 2018, 3% in 2019, 8% in 2020.