A year-round disease affecting everyone

What is influenza?

We know now that influenza, or flu, is caused by a virus – but for many years it was thought to be caused by a bacterial infection. In 1892, German scientist Richard Pfeiffer isolated a small bacterium from the noses of patients with flu, naming it ‘bacillus influenzae’.

Early attempts at a vaccine during the 1918 influenza pandemic were based on this understanding, and it was not until the 1930s, when the influenza virus was identified, that progress towards an effective vaccine could really begin.

Influenza – also known as the ‘flu’ – is a highly contagious respiratory illness, which spreads easily through the air or when people touch contaminated surfaces. In many cases the disease is mild, with symptoms such as chills, fever and fatigue, and it can also be spread through asymptomatic infections in people who do not even know they are sick.

But the flu can also result in serious complications, particularly in vulnerable people like young children, older persons, pregnant women and people with medical conditions such as asthma, diabetes or heart disease. The most common complication is pneumonia, typically caused by a secondary bacterial infection.

Flu viruses mutate very rapidly, and uncontrolled spread gives rise to many different strains, which fall into 2 main types affecting humans – influenza A and influenza B.

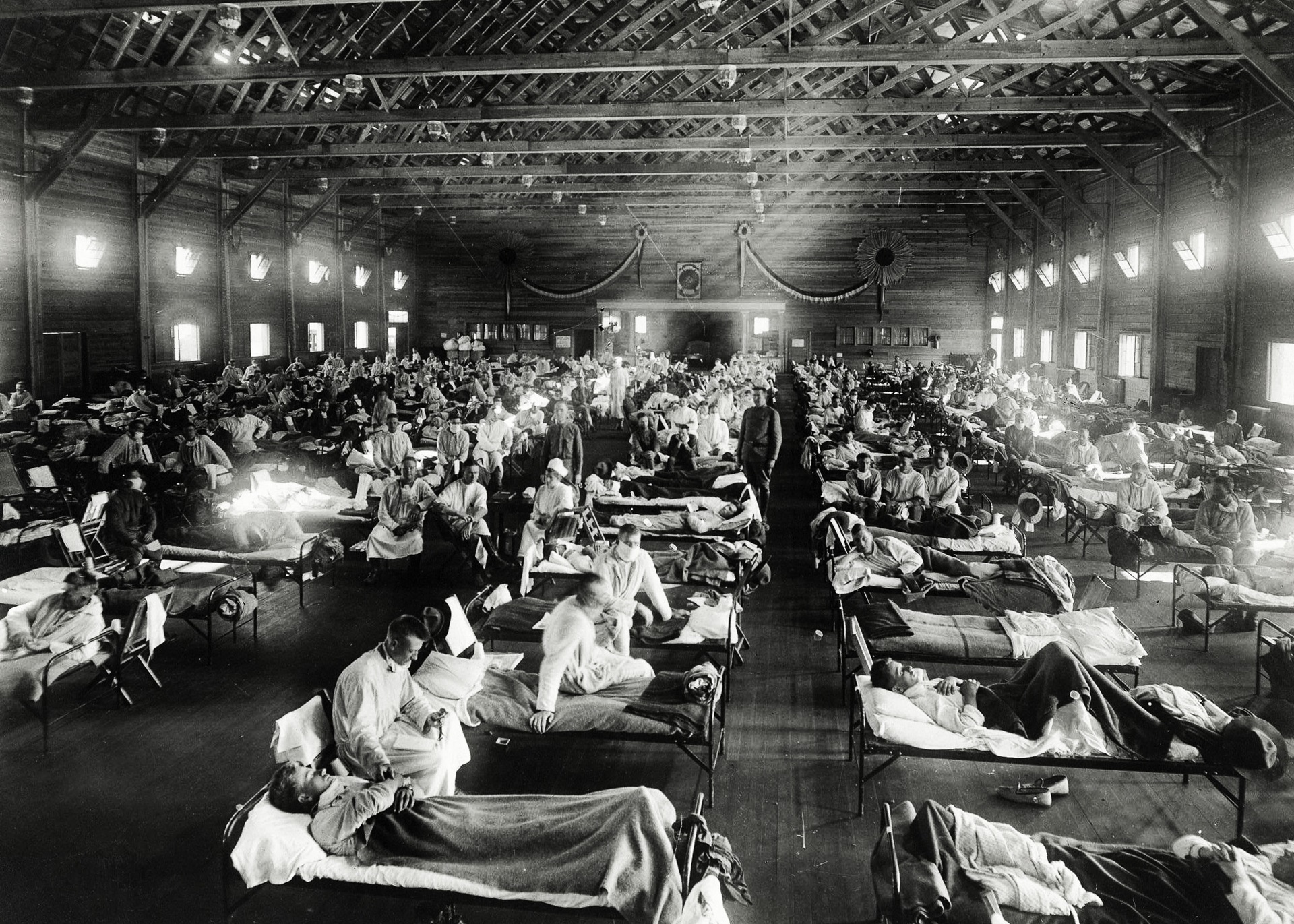

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas (1918).

“The mother of all pandemics”

The H1N1 influenza pandemic that swept across the world from 1918 to 1919, sometimes called “the mother of all pandemics”, involved a particularly virulent new strain of the influenza A virus. The first wave of infections in early 1918 resulted in mild illness, but a second wave later that year was more deadly.

The 1918 pandemic is estimated to have infected 500 million people worldwide, killing between 20 and 50 million. The resulting death rates were so high that life expectancy rates around the world dropped by several years, and more people are thought to have died as a result of the flu pandemic than over the course of the entire First World War.

Researchers in the United States and Europe raced to find an effective vaccine against influenza during the pandemic years, and their efforts produced hundreds of thousands of doses – but they were targeting the wrong pathogen.

The day starts at the World Influenza Centre, London, with a conference between Dr C.E. Andrews, Director (right), and his assistant Dr A.A Isaacs

Progress toward a vaccine

In 1933, British researchers Wilson Smith, C.H. Andrewes and P.P. Laidlaw at London’s National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) made a breakthrough when they isolated and identified the influenza virus. They found no bacteria in throat washings from patients with influenza and discovered that the disease was caused by a virus.

With support from the US Army, the first inactivated flu vaccine was developed by Thomas Francis and Jonas Salk at the University of Michigan. The vaccine was tested for safety and efficacy on the US military, before being licensed for wider use in 1945.

Miss H.B. Donald of Melbourne, Australia at the Siemeus electron microscope

Multiple strains

Researchers had long suspected that different types of influenza viruses existed, as the blood of some influenza patients did not develop antibodies to the strain isolated in 1933. During the testing period, scientists also discovered the existence of another strain of the virus: influenza B.

In 1942, a new bivalent vaccine was developed that protected against both the H1N1 strain of influenza A and the newly discovered influenza B virus.

During the 1947 flu season, researchers discovered that existing vaccines were ineffective against the flu viruses circulating at the time. To investigate the viruses in circulation, the World Health Organization (WHO) established the Worldwide Influenza Centre in 1948 and the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) in 1952.

Scientists could now manufacture vaccines based on the monitoring of virus strains in circulation around the world, updating the strains targeted by the vaccine in response.

Efforts to track the evolution and emergence of flu viruses continue today, and scientists monitor both seasonal and potentially pandemic flu strains. Because new strains appear frequently, the seasonal flu vaccine usually changes each year, as scientists determine how the virus has mutated and spread.

Each year, WHO recommends virus strains for inclusion in flu vaccines for each hemisphere, and different vaccines are developed, targeting 3 or 4 strains of the virus predicted to be most commonly circulating in the coming flu season.

This historic image depicts a line of people each awaiting a New Jersey Influenza vaccination. Also known as the Swine Flu, this image was captured during a 1976 immunization campaign

Potential for pandemics

Influenza pandemics have occurred throughout history: records document at least 3 well before the 1918–19 pandemic, and another 3 have taken hold after, in 1957–58, 1968–69 and 2009–10.

Influenza viruses with pandemic potential regularly emerge, but not all go on to cause a pandemic. WHO works to monitor influenza viruses with pandemic potential and to prepare for future influenza pandemics.

Lyon, France, 9 March 2022; Institute of infectious agents, University Hospital Lyon. A lab technician at work, seen through the automated PCR system instrument

Continued efforts

Researchers are constantly working to develop new vaccine technologies to keep a step ahead of the viruses.

A live attenuated vaccine delivered in the form of a nasal spray was first licensed in 2003, a vaccine using recombinant DNA technology was approved in 2013, and additional influenza vaccines based on newer technologies are being tested in clinical trials.

Despite these efforts, seasonal influenza still kills up to 650 000 people a year globally. Influenza is a constantly evolving virus, and immunity to a single strain through infection or vaccination does not necessarily protect against new strains that develop.

We know from experience there is likely to be another flu pandemic, and we should be as well prepared as possible when it happens. That’s why monitoring the virus and keeping up with vaccination is crucially important.

Watch this video to learn more about the history, symptoms and treatment of Influenza.

Related history of vaccination stories