Health risks

The housing sector has an impact on climate and health through its contribution to greenhouse gas and air pollution emissions. The design and quality of housing structures can also pose numerous health risks by way of exposure to extremes of heat and cold; insect and pest infestations; toxic paints and glues, and dampness and mould. Household cooking and heating systems can generate indoor smoke that is a source of cardiovascular and respiratory health risks, as well as cancers.

Housing has an impact on health and well-being through numerous environmental pathways. Key housing related environmental health risks include:

- household air pollution from cooking, heating and lighting, particularly rudimentary biomass and coal cooking and heating stoves;

- indoor air quality risks from dust or gases emitted by toxic building materials or radon exposures;

- exposure to extreme heat and cold;

- exposure to disease-bearing vectors, including pests and insects;

- exposure to damp and mould;

- lack of access to clean drinking-water and sanitation;

- outdoor air pollution – both from household emissions and other sources;

- urban siting and design features, which affect exposures to flooding and extreme weather; access to green spaces for physical activity; noise exposures; and access to transport routes;

- use of unsafe construction materials and poor construction practices.

These environmental factors impact on a range of disease and disability conditions, including:

- airborne infectious diseases, including TB;

- vector-borne diseases (e.g. malaria, Chagas, leishmaniasis);

- waterborne/diarrhoeal diseases related to unsafe water and sanitation;

- noncommunicable diseases, including risk of stroke, heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases (from air pollution as well as extreme temperature exposures;

- allergies (from mould and damp); and cancers, e.g. from radon exposures;

- domestic injuries;

- mental health and neighbourhood social cohesion;

- occupational health risks, ranging from injuries and falls to environmental exposures to toxic building materials.

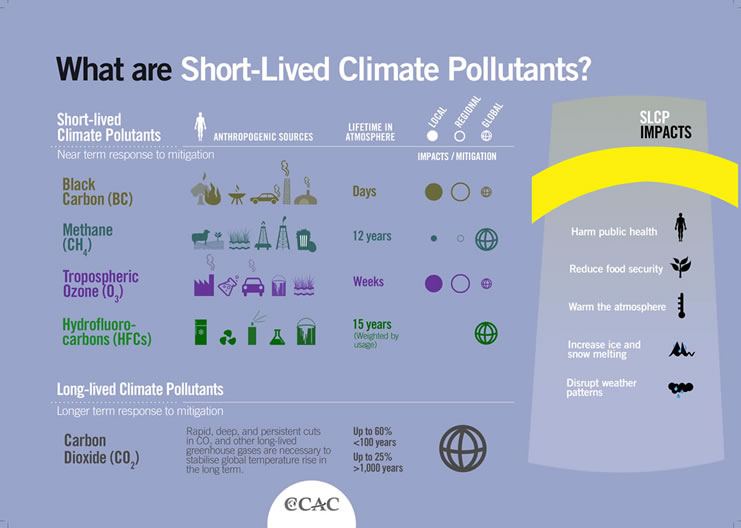

Additionally, inefficient household energy systems and household emissions from polluting kerosene lamps, cookstoves and heating systems not only diminish indoor and outdoor air quality, but also contribute to climate change through emissions of both CO2 as well as short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) such as black carbon and nitrogen oxides (NOx), further affecting health.

More sustainable housing designs can help reduce much of this burden of disease, providing health is considered in the siting, design, choice of materials, and construction.

Climate risks from CO2 and short-lived climate pollutants

Housing practices influence climate, which has an intimate relationship with health. The building sector (residential and commercial) accounted for 19% of global greenhouse gas emissions and one-third of global black carbon emissions in 2010, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2014).

Poor urban design, including residential neighbourhood design, exacerbates the “urban heat island effect” from sunlight reflected onto extensive paved surfaces, which can raise temperatures in city environments by 5-12 degrees Celsius. More urban heat island impacts, in turn, increase heat-related mortality risks, air quality, and as reliance on air conditioning – further contributing to climate change.

Exposure to extreme heat and cold

Cardiac failure, stroke and (in the case of cold exposure) respiratory infections are associated with exposure to temperature extremes, which can result from inadequate housing design and infrastructure. Poor household insulation, heating, or ventilation can exacerbate the effects of climate extremes. Frequently, poor households are the hardest hit, as the poor can least afford to adequately heat or cool their homes.

Determinants of cold indoor conditions include the dwelling’s age, heating costs, household income, household size, and level of satisfaction with the heating system.

Extreme heat conditions are linked to deaths from heat exhaustion, stroke, and cardiovascular disease. Heat waves are projected to increase in duration, and severity with climate change, an effect which has become apparent in recent decades.

Household air pollution from cooking, heating and lighting

Around 3 billion of the world’s poorest people still rely on solid fuels (wood, animal dung, charcoal, crop wastes and coal) burned in inefficient stoves for cooking and heating, and some 1.2 billion light their homes with simple kerosene lamps. These household energy practices emit large quantities of health-damaging particulate matter and climate warming pollutants (e.g. black carbon) into the household environment, increasing the risk of respiratory illnesses, including childhood pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular diseases, and lung cancers.

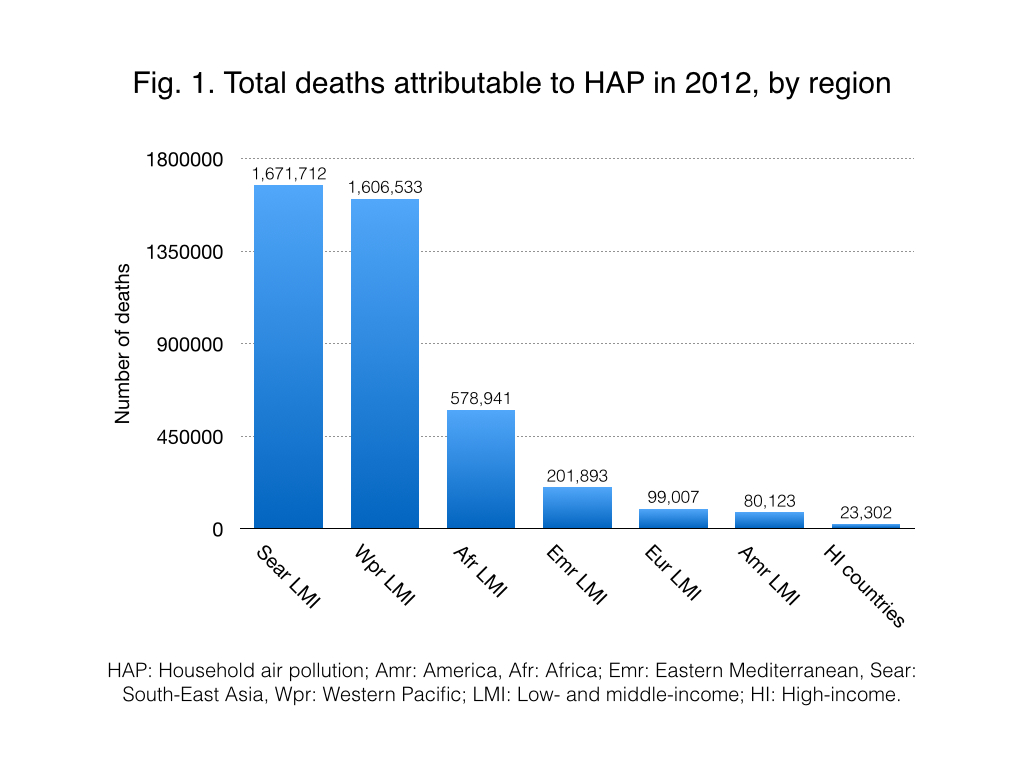

Global burden of disease estimates have found that exposure to household air pollution due to cooking on inefficient biomass stoves led to an estimated 3.8 million deaths in 2016. This does not include risks related to the use of inefficient lighting like candles or kerosene lamps. The data also does not consider deaths or diseases related to the use of coal, kerosene or biomass heating systems, which may also emit large quantities of particulate-laden smoke either directly into the household or outdoors into the neighbourhood.

Figure: Total deaths attributable to HAP in 2016, by region

WHO, 2012

The use of traditional fuels for household cooking, heating and lighting is also associated with a high risk of burns (e.g. from children falling into fires, spilled fuel, etc.) and poisoning (e.g. from children ingesting kerosene). Women and children may also be at risk for injury and violence during fuel collection. Fuel gathering may take many hours per week, limiting other productive activities and taking children away from school. Reliance on wood as fuel can also contribute to deforestation, especially in areas where fuelwood is scarce. Unsustainable wood harvesting can lead to forest degradation and loss of habitat and biodiversity.

In terms of heating systems, portable kerosene cookers and heaters emit significant particulate matter, including black carbon emissions, directly into the household environment, or outdoors. Portable gas heaters emit comparatively less particulate matter, but can still release excessive quantities of NOx into the indoor environment; they also pose risks for carbon monoxide poisoning.

Central heating systems, in which fuel is burned in a contained boiler to heat water or another circulation liquid, usually provide a clean indoor environment. However, systems that burn diesel or fuel oil tend to release significant particulate matter outdoors – contributing to ambient air pollution as well as to climate change – through both CO2 and black carbon emissions. Central heating systems that operate on natural gas or liquefied petroleum gas fuels generally emit far less particulate matter, including far less black carbon, as well as lower CO2 emissions.

Indoor air quality risks

Lead and asbestos, chemicals and radon, mould and moisture

Indoor air quality is also damaged by poor choice of building materials, structural risks as well as poor ventilation practices, as follows:

Moisture build-up, mould and bacterial growth can occur as a result of structural building faults, inadequate heating, insulation or inadequate ventilation. These can increase risks of allergies and asthma.

Radon is a radioactive gas that emanates from certain rock and soil formations, concentrating in the basement or ground levels of homes, in the absence of inadequate ventilation or evacuation systems. Recent studies on indoor radon in Europe, North America and Asia indicate that lung cancers attributable to radon may range from 3–14%.

Asbestos fibres, used in roofing and insulation, have significant carcinogenic effects upon exposed building inhabitants and construction workers. Asbestos use is still unregulated and prevalent in many developing countries.

Lead, still common in certain paints and pipe products in developing countries, has toxic effects and exposure to inhaled or ingested lead dust from has been linked to impaired childhood cognitive development.

Volatile organic compounds (VOC), including formaldehyde, may be emitted slowly from indoor building materials, furniture, paints and carpets. VOCs also may be released by smoking and detergent, or drift in from attached garages or outdoor sources. These can contribute to acute conditions (e.g. poisonings) as well as cancers and asthma. Compact fluorescent lights as well as thermostats commonly contain mercury and thus must be handled with care to avoid exposures, particularly when broken.

Risks of indoor air pollutants can be lowered by adequate natural ventilation as well as through the use of healthier building materials, including replacement or phasing out of hazardous building substances wherever possible.

Neighbourhood environments and urban form

The design and setting of neighbourhoods and urban environments also impacts health risks.

Dense urban settlements have been linked to health risks, such as airborne disease transmission. For instance, households with poor ventilation, poor sanitation, or crowding promote transmission of tuberculosis. Environmental noise exposures represent a health risk in areas of high housing density, transport-related noise, and proximity to industry. Exposure to high noise levels can cause sleep disturbance, stress and annoyance, cardiovascular problems, and potential hearing loss. Poor quality housing can also worsen anxiety, depression, social dysfunction, and other mental conditions.

Conversely, sprawling, isolated urban areas tend to limit accessibility for groups lacking independent mobility. In addition, obesity trends are linked to low-density urban designs which favour private vehicle transport. Neighbourhoods which lack open, green spaces and infrastructure for public transport and active travel have been associated with lower levels of physical activity. Mixed-use, medium density urban design can improve citizens’ independent mobility, safety, and access to physical and social activities, in turn increasing residents’ satisfaction with the environmental quality of their neighbourhoods.

See the Cities section of this website for further information on the health risks and benefits of neighbourhood environments and urban design strategies.

Pests, insects and vector-borne diseases

Poor housing structures, including cracks in roofs, floors, walls and eaves, as well as a lack of window and door screening, increase risks of vector-borne diseases carried by pests and insects, most notably malaria and dengue, as well as leishmaniasis, carried by sandflies, and Chagas, which is transmitted by crawling triatomine insects.

Climate change, deforestation and urbanization also have exacerbated the risk of transmission of dengue, malaria, tick-borne encephalitis, Lyme disease, and Chagas, in many parts of the world. Lack of adequate water infrastructure, drainage or sewage disposal can also increase transmission of malaria and dengue fever, providing breeding grounds near and around homes.

Waterborne diseases related to unsafe water and sanitation

Waterborne diseases are linked to significant disease burden worldwide. Climate change-induced flooding and droughts can impact household water and sanitation infrastructure and related health risks. For instance, flooding can disperse faecal contaminants, increasing risks of outbreaks of waterborne diseases such as cholera. In addition, water shortages due to drought can increase risks of diarrhoeal disease.

Proper household water and sanitation practices can increase resilience to waterborne disease risks. These measures include sanitary sewage disposal, safe water piping materials and storage, and education on hygienic behaviours. Energy-efficient water infrastructure and water conservation measures can also decrease the burden of waterborne diseases.

Publications

This document aims to provide the rationale for action to improve health through healthy environments, and an overview of key actions to take. It aims...

Health in the green economy : health co-benefits of climate change mitigation - housing sector

WHO's Health in the Green Economy sector briefings examine the health impacts of climate change mitigation strategies considered by the Intergovernmental...