More and more countries are taxing tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks as a public health tool. By reducing consumption of unhealthy products, health taxes are one of the most cost-effective measures to prevent diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes. Plus, they raise government revenue. However, they are often not ideally designed for health impact. Countries are also looking at other measures to improve diets and thus address a rising disease burden. In the Americas, there is a growing movement for warning labels on unhealthy foods. These recent trends and WHO’s role in driving them are the focus of this feature story.

Gaspar da Silva, 48, has not smoked since December 2022. The freelance artist from Dili, Timor-Leste, had noticed last year he was short of breath during singing performances and was not able to cycle for long distances. A recent hike in prices – a pack of 20 cigarettes of a popular brand has increased from $2 to US$3.50 – also provided the impetus to stop.

A smoker for 30 years, Gaspar was previously smoking at least two packs a day, even five packs when with friends. He had tried several times to stop without success; this time, he is getting help from the Formosa Cessation Clinic in Dili.

Timor-Leste has one of the world’s highest rates of tobacco use. With tobacco a major risk factor for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) that cause 65% of deaths in the country, the government decided to act. In 2022, they raised tobacco taxes, which were low, and doubled taxes again in January 2023.

The move is expected to cut cigarette sales substantially, while significantly raising revenue. The country’s four cessation centres, which have helped thousands of Timorese stop smoking, including Gaspar, will be expanded. WHO is providing support to the cessation centres, nicotine replacement therapy, and technical support and evidence on health taxes – including on sugary drinks – to the government. The sugar tax follows a 2020 survey that found nearly half of children under-five were stunted, due to diets poor in nutritious foods and high in junk foods and sugary drinks.

These bold actions, and the readiness to face challenges from industry, took immense political will from one of the world’s smallest countries, for which it has won much praise.

Health taxes a “win-win” for governments

Since 2017, at least 133 countries have increased or introduced a new health tax. The growing interest has seen WHO step up guidance to countries. Health taxes not only save lives and cut health costs, but raise hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue globally. They are also less costly to implement than other interventions to prevent NCDs. And they are pro-poor, as they particularly reduce consumption among lower income households, so benefit the poor most in averting NCDs and associated costs.

Cutting consumption of tobacco, sugary beverages and alcohol could prevent at least 11 million premature deaths annually from NCDs – over one in five global deaths.

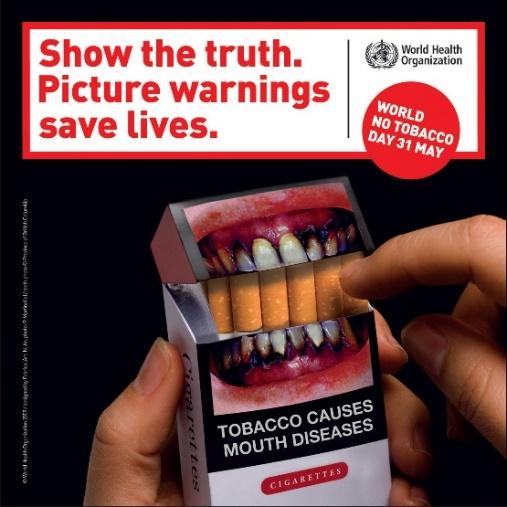

Tobacco taxes are the most cost effective measure to reduce tobacco use, which kills more than eight million people a year. In fact, they are one of the most effective health policies to prevent premature deaths. They also deter youth initiation, which is important in countries with young populations like Timor-Leste.

Taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are gaining momentum. Countries are seeking policy tools to address the massive rise of obesity and diet-related diseases such as diabetes, propelled in part by SSBs and ultra-processed food products becoming more available and affordable.

The rationale for SSBs taxes is clear. SSBs are a major source of excess sugars, with little or no nutritional value. Excess consumption can lead to obesity, diabetes, heart disease and dental caries.

Currently, more than 85 countries have some form of SSB taxes, including three-fifths of all Member States in the WHO Americas Region and half of all countries in WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. However, there is huge heterogeneity in tax design and products taxed, as a study on SSB taxes in the Americas found, with a need for better design for health benefits.

Impact of health taxes in countries:

Colombia: Cigarette consumption fell by 34% in 2018 after excise taxes were tripled, while revenues (earmarked for health) doubled. Prior to 2016, the country had the second-cheapest price for cigarettes in the western hemisphere.

Mexico: A 1 peso per litre (about 10%) tax on SSBs introduced in 2014 has successfully sustained sales reduction over time, resulting in savings of $4 in healthcare costs per dollar spent on tax implementation.

The Philippines: Tobacco use prevalence fell from 30% in 2009 to 20% in 2021, a change driven by significant, continued tax increases, alongside other tobacco control measures.

Designing taxes for health

Although tobacco and alcohol taxes are far from new, they are surprisingly underutilized. They are often designed with a revenue rather

than a health objective (especially the case for alcohol). Most countries simply do not impose health taxes at high enough levels. In 2020, only 40 countries had sufficiently high tobacco taxes. This is in part due to interference from the tobacco industry.

It is important to set the right tax rates and structure, adjust for inflation and income growth, and to have a strong tax administration. For SSB taxes, they can be structured to reduce consumption, or tiered by sugar content, which can drive companies to change or reformulate products and consumer intake towards unsweetened beverages, WHO’s new global SSB tax manual notes. Also, of various tax options, excise taxes are key for health, as they impact costs onto consumers.

Although powerful alone, health taxes are best applied as part of a package of interventions. Taxing tobacco is just one of six strategies of MPOWER, WHO’s package for tobacco control, while SAFER is WHO’s alcohol control package. At least one MPOWER measure is in place in 146 countries. Yet the least implemented is one of the most cost-effective health policies: tobacco taxes. Many countries have yet to realise the value of health taxes in saving lives and raising revenue.

Health taxes having an impact in Gulf countries

Until recently, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries relied on import duties for revenues from tobacco, but these were low and falling, due to trade agreements. In 2016, GCC countries agreed on a harmonized excise tax on tobacco products. With continued increases and WHO support, the tax share reached over 60% in 2022. An evaluation initiated by WHO found a notable drop in cigarette sales in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, setting an example of effective taxation in the region.

GCC countries have also introduced an SSB tax. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, this led to soda prices rising by 67%, resulting in a drop in annual purchases, in volume per capita, of soda drinks by 41% in 2018 compared to 2016.

Strong food labelling laws in the Americas

Obesity rates have increased almost five times in children since 1975

The Americas has the highest prevalence of obesity among WHO regions, with 64% of men overweight or obese.

Obesity rates have increased almost five times in children since 1975

The Americas has the highest prevalence of obesity among WHO regions, with 64% of men overweight or obese.

Aside from taxes, countries are also working to improve food environments through a number of different policies, including marketing and labelling laws. Thailand for example, has advanced a draft legislation on marketing restrictions of unhealthy foods and beverages to children for public hearing.

Policies on food composition, such as on sodium levels or trans fats, are also proliferating. Since WHO called to eliminate industrially-produced trans fat in 2018, 60 countries have implemented policies limiting the use of trans fat in food, protecting 3.4 billion people globally.

Food labelling aims to enable consumers to make informed choices for healthier food products through providing information on nutritional content.

Chile started the ball rolling in 2016. Faced with high and rising obesity levels, (then reaching one in every three adults and one in every four children), the government made it mandatory to have warning labels on food packaging.

Black labels, shaped in stop signs, warn consumers if products contain high levels of sugar, salt, saturated fats or calories. Under the law, foods with warning labels cannot be sold in schools or marketed to children. Marketing restrictions also require companies to remove popular cartoon characters from packaging of foods with warning labels.

The industry battled hard against the law, challenging its legality before the courts. But the government prevailed and the measures remained. Companies then began to reformulate their products to avoid having warning labels. The Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), WHO’s Regional Office for the Americas, has helped Chile sustain the policy with technical and legal support, and continues to do so with guidance to further improve the policy.

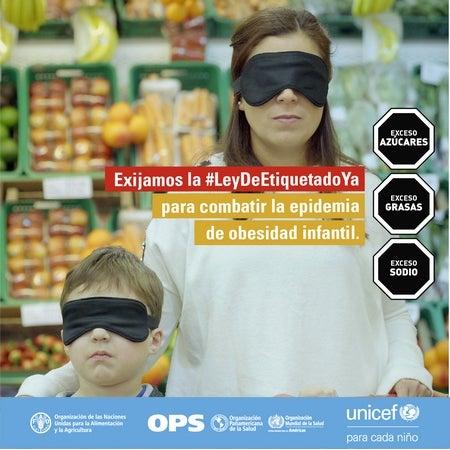

The PAHO/FAO/UNICEF campaign calls for warning labels to uncover consumers’ eyes to information on the content of food products. Etiquetado frontal de advertencias en Argentina - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud (paho.org)

Mexico also adopted the black warning label system of Chile, as seen here

Studies have shown Chile’s measures have improved consumers food choices – they reduced purchases of products high in sugar, calories and sodium by 27%, 24% and 37% respectively within the first 18 months of implementation. There is also evidence that the warning labels convey information on unhealthy nutrients more effectively than other labelling systems, such as the “traffic light” and other systems that may serve as endorsement of products, which in some cases can confuse or mislead consumers.

Chile’s landmark law moved the needle on the issue. Argentina, Colombia and Mexico have since evolved the policy to make it even more effective, improving the design of warning labels and defining unhealthy products – subject to the warnings – using the PAHO nutrient profile model. Today, all 35 countries across the Region have discussed front-of-package labelling, 11 countries have formally adopted it and 7 countries have started implementing it.

It has not all been smooth sailing. Manufacturers have tried to block or obfuscate regulations or lobby lawmakers. Yet strong political will and public participation across the Americas, as well as consistent support from PAHO/WHO, provided the elements that ensured one country’s efforts to fight obesity has now transformed into a regionwide – and possibly global – movement that will impact millions of people.

Trend of healthy eating laws in the Americas

In 2022, Argentina implemented one of the world’s strongest and most comprehensive laws on food policy. The law adopts the PAHO/WHO food classification tool to define products subject to warning labels and prohibition of marketing, promotion, sponsorship, sale in schools, and public food procurement. Consumers are now alerted to unhealthy products with large octagonal black warning labels, in an improvement of Chile’s labelling system.

Mexico, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) have also implemented warning labels. Colombia is set to start implementing its healthy eating law soon; Boliva (Plurinational State of) and Paraguay are in the process of adopting their law; Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Panama have started tabling drafts of their healthy eating laws; and the Caribbean is discussing a subregional standard for warning labels.